By musicologist Professor Zumrud Dadashzade

We have overcome in decades what others have done in centuries. Yet, we need to study world experience more deeply… After all, we are also a part of the world, and our work today is part of the work of all humankind…

These words belong to the outstanding representative of Azerbaijani culture, composer Gara Garayev (Qara Qarayev) (1918-1982). Azerbaijani music should take its rightful place among the highest achievements of the musical culture of the 20th century – that was the composer’s cherished dream. Moreover, the whole life of the master, all his multifaceted activities were devoted to the realization of this dream.

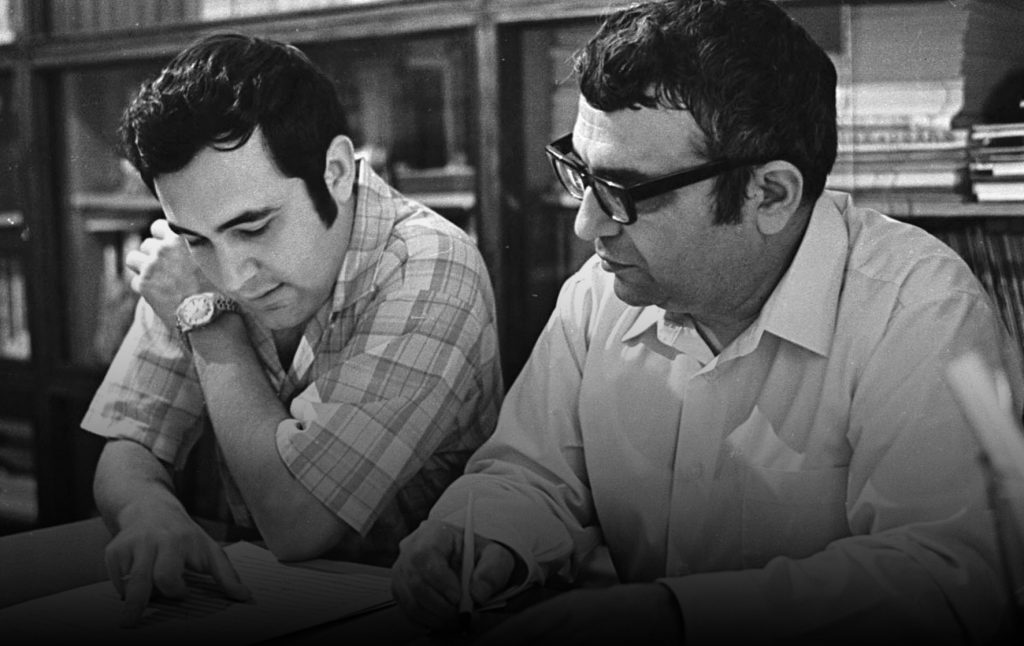

The brilliant artists of the 20th century – the founder of the Azerbaijani composers’ school, Uzeyir Hajibeyli(Üzeyir Hacıbəyli), and the great Russian symphonist Dmitry Shostakovich played a huge role in the formation of Gara Garayev.

Garayev learns the beauty and depth of Azerbaijani traditional music in the class of Hajibeyli. Garayev later spoke about the role of his mentor in his life: “He, as they say, fought for my national soul.”

At the Tchaikovsky Moscow Conservatory, in the class of Shostakovich Gara Garayev comprehended the secrets of the composer’s craft and joined the most important achievements of world music.

Gara Garayev joined the creative path in the second half of the 1930s – an important, decisive period for the further fate of the musical art of Azerbaijan.

Following in the footsteps of Uzeyir Hajibeyli, Gara Garayev at a qualitatively new stage in the history of Azerbaijani music began to search for ways of organic synthesis of national traditions with the achievements of world culture. “West and East were close to me from the very beginning” – this phrase is the essence of the composer’s worldview.

The first great success came to Gara Garayev in 1947, when he created the symphonic poem “Leyli and Majnun” based on the motives of Nizami Ganjavi. The pinnacle of Gara Garayev’s creativity is two ballets – “Seven Beauties” (1952) and “The Path of Thunder” (1958).

Here the composer, masterfully implementing the traditions of classical ballet, relying on the experience of Tchaikovsky, and Prokofiev, as well as creatively applying the features of the musical and choreographic art of Azerbaijan, created innovative works, marked by dramaturgy integrity, a truly symphonic features of development. By embodying complex themes of philosophical, and social sounding in ballets, Gara Garayev significantly expanded the boundaries of the possibilities of this genre.

In the ballet “Seven Beauties”, starting from the main ideas of Nizami’s Khamsa (Quintet), Gara Garayev created a musical and choreographic poem about the fate and aspirations of the people, about the beauty of the human person, about ethically sublime love.

In the ballet “The Path of Thunder”, based on the novel of the same name by the South African writer Peter Abrahams, for the first time on the ballet stage, one of the most pressing themes of our time has found its embodiment – the theme of the struggle against colonial slavery and racial inequality. However, despite the importance of the socio-political context, the main idea of the ballet is love, destroying a seemingly insurmountable barrier, and defeating the enmity, generated by human prejudices.

The composer’s forward-thinking creative searches were not always perceived unambiguously. Sometimes contemporaries, being unable to understand the innovative essence of the symphonic poem “Leyli and Majnun”, the ballet “Seven Beauties”, symphonies, and the Violin Concerto, reproached the composer for violating the modal and intonational norms of Azerbaijani music.

But the whole issue was in a new reading of national traditions by Gara Garayev. The composer sharply condemned the consumer attitude to folklore: “Let’s admit, aren’t we getting it too easily, folk music,” he said, “are we using the upper, easily accessible layers too ruthlessly, isn’t it time to think about the fact that folk music is indeed inexhaustible, but its main riches are not only on the surface, but lie much deeper than we think, and it is time for us to get to them, armed with the necessary ‘technical devices’”.

At the same time, neither the complexity of “technical adaptations” nor the figurative polyphony of Garayev’s creativity could obscure the deeply national essence of the master’s music, which sometimes reveals itself at the level of thinking.

In one of his interviews, Gara Garayev notes: “National traditions are sometimes manifested in creativity unconsciously. I write music on Spanish, Bulgarian, and Vietnamese topics, and they tell me that it bears the imprint of my nationality, my Azerbaijani hands. How this happens – I cannot explain and do not think about it.”

A friend of the composer, writer Imran Gasimov, admiring the breadth of Gara Garayev’s horizons, emphasized that no matter what the composer was talking about, the impression was created that “Garayev hold whole civilization in the palm of his hand, and not in elementary encyclopedic information, but in deep knowledge – in nine occasions out of ten – in a strikingly original interpretation – a kind of lens in the brain that refracts the informational ray in a completely unexpected perspective”.

An intense spiritual life and a wide range of hobbies were reflected in the variety of themes and style models used by the composer. Gara Garayev was attracted by the world of literary images of Nizami and Shakespeare, Omar Khayyam and Pushkin, Cervantes and Nazim Hikmet, Langston Hughes and Mikhail Bulgakov, Edmond Rostand and Samad Vurghun.

Every time new themes, and new images brought to life new means of expression, and new artistic solutions. The bright, sparkling colors of the ballet “The Path of Thunder” side by side with the restrained graphic features of the symphonic engravings “Don Quixote”, the artless genre of the “Albanian Rhapsody” – with the music of the String Quartet stylized in the classicist spirit, the emotionality, romantic imagery of the symphonic poem “Leyli and Majnun” – with intellectual lyrics of the Violin Concerto.

Simultaneously, Gara Garayev, first, was attracted by themes, consonant with the times. “Modernity excites my soul especially deeply. And maybe I would never have become a composer, had I been born in the old days,” the composer admitted.

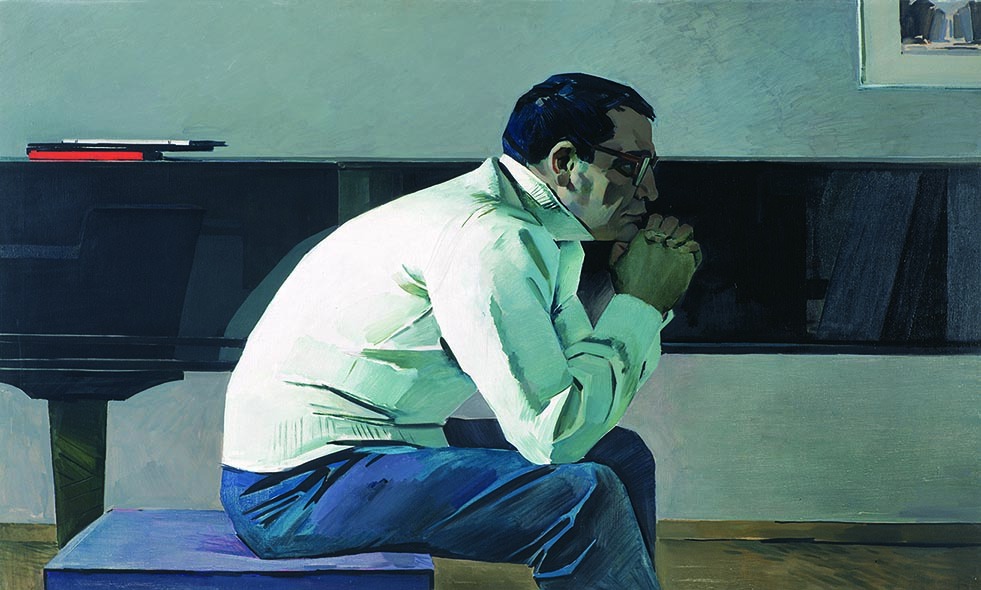

Considering the work of Gara Garayev, it is impossible not to touch on the topic of “an artist and time”. The complex, contradictory time, in which the composer lived, clearly emerges both in the direction of creative searches, in the topics discussed, and in the twists of fate.

Outwardly, Gara Garayev’s biography looks cloudless and happy. By the age of 50, he was awarded many honorary titles and prizes, including the most prestigious Lenin Prize, crowned with the laurels of a classic of Soviet music. However, behind the beautiful facade, a somewhat tragic fate looms – the fate of an artist in a totalitarian country.

In 1948, after the infamous Decree of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks “On the opera ‘Great Friendship’ by V. Muradeli”, Gara Garayev, twice awarded the State Prize by this time, was ranked among the formalist composers and was sharply criticized in the press.

Gara Garayev was accused of ignoring the traditions of national and classical music, the abstractness of the melodic language, and the abundance of chaotic dissonant harmonies.

The 1960s, marked by a warming of the political climate, were there with the elimination of the “Iron Curtain” between the USSR and the West, and, as a result, the penetration of more information into the country. Criteria began to change in life and art, much, even in the recent past, was reassessed, and the hearts and minds of musicians were taken over by new idols – Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, representatives of the avant-garde of the second wave.

The early 1960s in the life of Gara Garayev was a difficult period, accompanied by heavy reflections, and doubts about the direction of creative searches. In a letter to the playwright-librettist Yuri Slonimsky, Gara Garayev spoke very sharply about his work of the 1940-50s: “The criteria in ethics and aesthetics have become completely different… Everything that I wrote and did before seems to me naive, stupidly enthusiastic, and overly explicit.”

Gara Garayev’s doubts were exacerbated by the impressions of the music he heard at the First International Los Angeles Music Festival (1961). The major outcome of this American trip was a sad and disturbing confession: “In art, we are 50 years behind.”

The panorama of the musical works presented at the festival struck the composer, first of all, with the variety of individual interpretations of the Schoenberg method. At the same time, what he heard in Los Angeles became a kind of catalyst, and stimulated him to creative searches. “In music, I mercilessly broke myself,” he wrote in one of his letters.

The creative results of this “break” were more than convincing: The Third Symphony (1964) and the Violin Concerto (1967) became landmark musical works of Soviet music, putting forward Gara Garayev to the forefront of the Soviet avant-garde artists.

Rodion Shchedrin, emphasizing the role of the composer in updating the aesthetics of Soviet music, writes that, thanks to Gara Garayev, music in the country “began to develop in a much more natural way than it was before”.

In the Violin Concerto, his most confessional composition, devoid of national signs at first glance, Gara Garayev managed to embody something more significant – the principles of national musical thinking. Did the emotional side of Garayev’s music suffer in the compositions of the 1960s?

Answering this question, one should note that even in the early works of the master, with all the generosity, and colorful emotional palette, according to the musicologist Leo Mazel, “it is not the element of sensuality that dominates, but deep psychologism, subtle intellect”. The philosophical content of the Violin Concerto revealed the intellectual power of oriental art, which is called “oriental wisdom”.

Being a great composer, Gara Garayev simultaneously happily combined the qualities of an outstanding teacher and scholar, and public figure. After the death of Uzeyir Hajibeyli (1948), Gara Garayev headed the Union of Composers of Azerbaijan for 30 years, was the rector of the Azerbaijan State Conservatory (1949-53), professor (1959), head of the department of composition, full member of the Academy of Sciences (1959).

Gara Garayev entered the history of Azerbaijani music as the creator of a new national school of composers. Rauf Hajiyev, Tofig Bakikhanov, Arif Malikov, Khayyam Mirzazade, Vasif Adigozalov, Mammad Guliyev, Faraj Garayev, Polad Bulbuloghlu, Aydin Azimov, Frangiz Alizade, Ismayil Hajibeyov, Rahilia Hasanova, Elnara Dadashova, Jalal Abbasov, and many others graduated from the class of Gara Garayev – overall, about 70 students! In general, Garayev always sought to lend a helping hand to talented youth, to all those “who profess the truth”.

The figure of Gara Garayev in Azerbaijan has acquired almost a cult value and is surrounded by love and respect. One of the Baku avenues, a metro station, a ship, an art school, and the State Chamber Orchestra are named after him. A monument to the composer has been erected in one of the central squares of Baku.

Musical offerings are being created, an International Contemporary Music Festival is named after Gara Garayev, and the concert program “Gara Garayev’s circle” was prepared (author – pianist Rena Rzayeva). This program demonstrates the boundlessness of the composer’s circle, in which more and more young musicians fall into the zone of attraction.

The year 2018 widely marked the centenary of Gara Garayev by order of President of Azerbaijan Republic Ilham Aliyev in the country and abroad. It was then that the opening of the composer’s apartment and museum in a house on Nizami Street. In this apartment, Gara Garayev spent his early, and youth years as well as created the first significant symphonic and chamber works, the opera “Vetén” ([Homeland] together with Jovdat Hajiyev).

The director of the museum is the daughter of the composer, an excellent musician, and teacher Zuleykha Garayeva-Baghirova, who for more than 20 years was in charge of the piano department of the school at the State Conservatory of the Istanbul Technical University.

Thanks to the efforts of Zuleykha khanim, the space of the museum has turned into a significant cultural center of the city of Baku, where musical evenings, presentations of new publications are held, creative information is exchanged, and young performers demonstrate their skills. In July, a new project, “Music of the 20th Century”, was launched at the museum. Of course, the works of Gara Garayev are often heard here, performed by both masters and students.

In February 2023, on the eve of the 105th anniversary of Gara Garayev, a recording of a ten-year-old Moscow concert was listened to, where his landmark works were performed by the Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra: the orchestra was led by Elshad Baghirov, Honored Artist of Azerbaijan, who worked as a conductor for many years (since 1986) at the Istanbul Opera and Ballet Theatre.

His interpretations of the works of Gara Garayev – they play a significant role in the conductor’s repertoire – are distinguished by their piercing, deep penetration into the author’s intention, which often leads to the disclosure of new facets of well-known music. E.Baghirov, the first of the Azerbaijani conductors, turned to the Violin Concerto of Gara Garayev, and was the artistic director and conductor of the ballet performance “Niçin?” (“Why?”), set to the music of the ballet “The Path of Thunder” by Gara Garayev at the Istanbul Theater (the author of the new libretto is choreographer Oytun Turfanda).

The traditions of the great musician are continued by his son and student, Faraj Garayev, People’s Artist of Azerbaijan, professor of the Moscow Conservatory, who is celebrating a significant anniversary in 2023.

Faraj Garayev is an iconic figure in modern music, an original composer who develops the deep-national branch of Gara Garayev’s creativity, and brought qualitatively new images to Azerbaijani music.

In his grand symphony “Tristessa” (Farewell Symphony), dedicated “to father, teacher, and friend”, F. Garayev creates his quivering music in dialogue with the spiritual world of Gara Garayev. In addition, when at the end of the work one of the most penetrating preludes (cis-moll) of Garayev-the father sounds, we are deeply shocked, realizing the irreparability of the loss…

In the third generation, the son of Zuleykha khanim and Elshad Baghirov, Zulfugar Baghirov, showed his talent, who graduated from the Berkley College of Music in Boston, with and master’s degree at New York University in composition and jazz performance. Zulfugar often gives concerts and teaches at the NOVA University of Washington.

The album “QaraBağ” speaks eloquently about his absolutely original, bright talent as a saxophonist and composer (the combination of the initial letters of two surnames – Garayev and Baghirov – Zulfugar’s paternal grandfather Zakir Baghirov was also a renowned composer – formed the name Garabagh, a region that occupies a special place in the heart of every Azerbaijani, the cradle of Azerbaijani culture), created in a duet with a pianist Renato Diz.

Boldly, sometimes paradoxically reinterpreting the iconic works of Azerbaijani music in a jazz style (for example, the overture from the opera “Koroghlu” by Hajibeyli, “The Most Beautiful” from the ballet “Seven Beauties” by Gara Garayev), the musicians reveal their new meanings, consonant with the times.

Concluding my thoughts about Gara Garayev, I would like to turn to the statement of Shchedrin from his book “Comments on the Past”: “Garayev took very close to his heart everything that happened on earth, in music, in his native Baku. He was not indifferent or apathetic to anything. Everything that happened became part of his body, brain, heart, lungs, aorta… Such was the property of his nature”.

I also recall the lines of the composer’s friend, Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet, “If I don’t burn, if you don’t burn, if we don’t burn, how the light vanquishes the darkness?” – perfectly expressing the essence of Garayev’s character.

Therefore, I ask myself a question: maybe we lack an excited, principled, and honest – Gara Garayev attitude to our problems, to art, to our profession? Therefore, we simply need to turn to the legacy of Gara Garayev more often, to compare everything done with his precepts.

Turn to the work of the Great Master, who never allowed dilettantism, “spontaneity of content”, “and sentimentality offensive to people.” Then, perhaps, something in our musical culture will change for the better. Listening to the music of Gara Garayev day after day, perhaps we will become a little more tolerant of each other, a little cleaner, nobler, and kinder – better.

- Gara Garayev. “Don Quixote”, symphonic engravings. The Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra. Elshad Baghirov, conductor

- Gara Garayev. Violin concerto. The Tchaikovsky Grand Symphony Orchestra. Aliona Bayeva, violin. Elshad Baghirov, conductor

- Gara Garayev. Dance from the ballet “Seven beauties”. The Gara Garayev Azerbaijan State Chamber Orchestra. Elshad Baghirov, conductor

- Gara Garayev. Prelude in A Major. The Gara Garayev Azerbaijan State Chamber Orchestra. Elshad Baghirov, conductor

- Gara Garayev, Faraj Garayev. “La quinta del sordo” (“Goya”), for symphony orchestra and choir. The Symphony Orchestra and Combined Choir of the Moscow Conservatory. Anatoly Levin, Conductor

- Gara Garayev. Waltz from the ballet “Seven Beauties”. The Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra. Elshad Baghirov, Conductor

- Wayne Shorter. Footprints played by Zulfugar Baghirov (saxophone) and Renato Diz (piano)